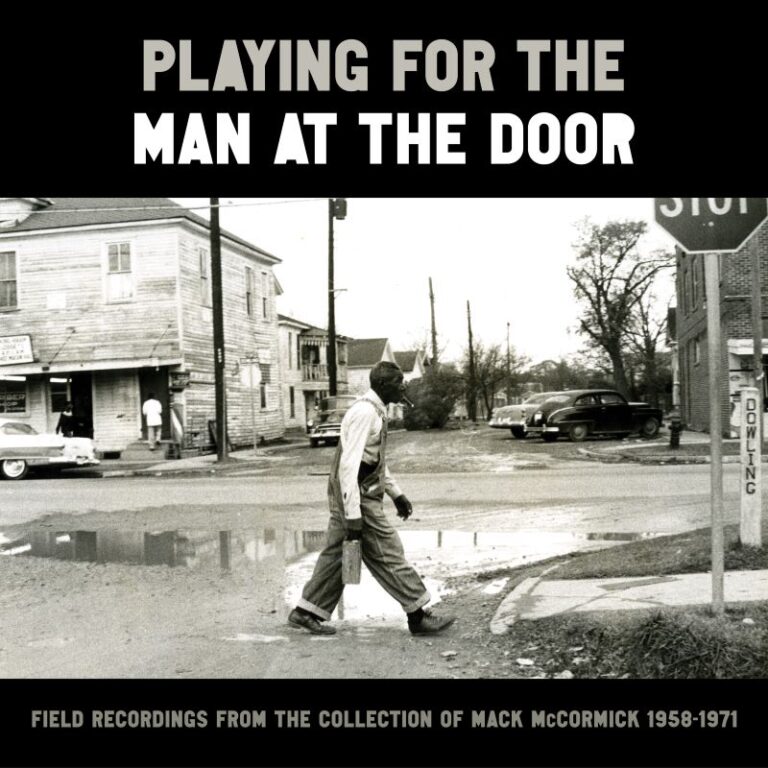

Album Review: ‘Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958-1971’

For decades, chasing the ghost of Mack McCormick resembled McCormick’s own epic quests to chase down the blues, jazz, spirituals, and other kinds of music and spoken word rhythms that shaped the homes and communities through which he traveled in “Greater Texas” (which included his forays into Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas). “He’s been a legend my entire career,” recalls Jeff Place of Smithsonian Folkways Records and co-producer with John Troutman, of the National Museum of American History, of the new box set Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958-1971.

Scholars, archivists and folklorists have long known that McCormick spent much of his life collecting field recordings, but no one had ever heard them or seen them. Says Place, “He kept them to himself.” Now, for the first time, in this three-CD/six-LP box set, we have the chance to hear some of these previously unheard field recordings.

In 2019, after a year of conversations, McCormick’s daughter Susannah Nix donated her father’s papers and recordings to the Smithsonian Institution. Over the next year, archivists organized the material. As Place observes, “We listened to and organized 590 reel-to-reel tapes. About 290 of these were field recordings of music and interviews he had conducted. Ronnie Simkins who plays with the Seldom Scene copied these and engineered them. Out of this we selected the 66 tracks in this set.” In addition to these recordings, the treasure trove of McCormick’s contained over 4,000 photographs, and over 90-liner feet of McCormick’s manuscripts and research notes.

In the mid- to late ‘40s, McCormick devoted his work to jazz, serving as the Texas editor for Orin Blackstone’s celebrated Index to Jazz. McCormick then became the Houston correspondent for Downbeat magazine in 1948. Over the next few years, McCormick worked a variety of odd jobs, but by 1957 he was driving cabs, giving him the opportunity to drive around looking for the 78s he loved and for the artists whose voices he heard on them.

McCormick turned to collecting field recordings in the 1950s and 1960s, gathering acoustic blues, piano boogie-woogie, and electric blues, as well as collecting pitches for medicine shows, recipes, and other non-musical artifacts from the rural men and women whose trust he gained. In many ways, though, Place points out, McCormick didn’t consider himself a collector and wasn’t concerned with disseminating the elements in his archives. “His recording was not about making records; it was about getting material so he could write about the musicians.” In 1969, McCormick started work on a biography of Robert Johnson, but because of a number of challenges—including his own struggles with bipolar disorder—he never completed it in his lifetime. Troutman worked with the existing draft and notes in the archives to produce an annotated version, with 40 never-before-seen black-and-white photos recording McCormick’s work, published in April as Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey.

Playing for the Man at the Door comes out on Friday, August 4, and offers a glimpse into the variety of styles and artists whose music McCormick collected. The set contains several tracks by Lightning Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb. Says Place, “while Hopkins and Lipscomb will be the best known in the set, we tried not to fill it with their music and to represent the great variety of styles he recorded.” One of them is Robert Shaw’s piano boogie-woogie, “The Clinton,” that refers to a famous stopping place at a junction of the Santa Fe railroad lines in Oklahoma. “Piano players,” says Place, “had to play in towns along railroad lines. The pianists could lug their instruments with them, of course, so the bars would have a piano where the piano players could perform as they moved from town to town. So, a lot of the titles of these songs are about railroad lines.”

Other songs on the set include spirituals such as “My Work Will be Done,” a rousing call and response number by The Spiritual Light Gospel Group, and acoustic Cajun-inflected pieces such as the rolling, striding “St. James Infirmary” by Dudley Alexander and Washboard Band.

One of the most interesting tracks is Joe Patterson’s “Quills,” featuring Patterson on guitar and quills, a wind instrument made of cane strapped together resembling pan pipes. The set features a number of tracks by slide guitarist Cedell Davis, including boogie blues “It’s All Right” and his raucous version of “Rollin’ and Tumblin’.” The box set also features political pitches such as George “Bongo Joe” Coleman’s sing-song pitch for his presidential candidacy on which he accompanies himself on steel drum, as well as Murl “Doc” Webster’s “Medicine Show Pitch.”

Playing for the Man at the Door reveals the breadth and depth of McCormick’s collecting. As Place puts it, “people would open up to him and talk about music and other things.” The box set offers insight into the music of a time and places and uncovers for us even more knowledge about the blues and the contexts that produced it. This is a collection that richly repays repeated listening, and the 128-page booklet that accompanies the set, with essays and liner notes by Place and Troutman, Dom Flemons, Nix, and blues scholar Mark Puryear provides listeners with in-depth information about McCormick’s life and work and the background of the songs in the set. This long-awaited set lives up to the anticipation it’s created.

###

Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958-1971 is available HERE